I Want to Tell You About My Friend

I don’t want to tell you that Stephenie Gaustad was a great spinner. Everyone knows that.

I don’t want to say she was a talented and generous fiber artist. If you have ever taken a class with her or read one of her books or articles, you already know that too.

I want to tell you about how warm her hugs were and how she never let go first. I want you to know how funny she was, how her eyes twinkled when she smiled, how she followed her heart in all things, and how she loved getting in good trouble. I want to tell you about the Stephenie I knew and how much I loved her.

The first time I fell into the arms of Stephenie Gaustad was at SOAR in 2010. Her flax to linen workshop was next to my textured yarns workshop. When I got to the part of the class where I have everyone spin a thick and thin singles yarn from cotton, a spinner in my class (who had recently taken a class with Steph) hopped up and ran out the door.

The retting sounds from next door halted, and Stephenie Gaustad walked through the adjoining classroom door.

“What’s this about spinning cotton thick and thin? Handspun cotton needs to be spun fine, with lots of twist, and very even.”

I was not a cotton spinner. My spinning skill was not nearly at the cotton “spun fine, with lots of twist, and very even” level. I only used cotton as an (extreme) example of how you can spin any combed fiber into a thick and thin yarn if you pay attention to the staple length.

I haltingly and nervously explained that even the shortest cotton can create a stable thick and thin singles yarn as long as you make your thick section shorter than the staple length so that the ends of the fibers are caught in the high-twist thin section on either end of the thick bit. I demonstrated as Stephenie (along with all my students and hers) stood around my wheel watching.

When I finished, she whooped!

She whooped and hugged me, and we never saw each other again when we didn’t hug and huddle up.

Because we both made a living travelling to teach, we saw each other often. One evening, after several days of teaching, we sat next to each other, exhausted, in a Chinese restaurant. I leaned in and whispered to her all my plans for starting a magazine. She smiled and her eyes twinkled. You have never seen such a twinkle.

When the first issue of PLY came out, she sent me a short length of handspun thick and thin cotton and a letter:

Dearest Jacey, Ply is fantastic! I love that you have multiple voices on a single topic, and really hear the person as he/she takes time with answers. This is what strikes me first. I get the chance to focus on something, spend time with it and not rush off in another direction 2 pages later. I treasure this copy and will refer back to it time and again.

-Stephenie

Your enthusiasm for the craft and project is palpable too. It is so exciting. I feel transported back in time, actually to a decade when new magazines were popping up right and left, in different formats; it all was new and fresh. Ply is a breath of fresh air!

Now it is time for Alden to add his 2 cents.

Well, I am flabbergasted. The scope of the work is mindboggling. The possibilities are limited only by your imagination and energy. The mag is a visual knockout, the advertising is arranged with taste and finesse and considering the stated purpose “the magazine for handspinners” what can I say but bravo! Huzzah! You are a phoenix rising in a world of turkeys.

-AA

From that first issue on, Stephenie was in almost every single issue of PLY and she and I were firm friends. I don’t even know if that’s true. I feel like I wasn’t friends with Stephenie – we were family. She was the closest thing I had to a grandmother, and when my mom died, she was there for me. Stephenie’s hugs were the warmest and she’d hold on as long as I needed.

Of course there were other things, business things, that happened – she became PLY’s technical editor, she taught at PLYAway every year, she wrote a wonderful book with us. But it’s the actual time I spent with Stephenie, the moments, that I remember and that mean the most. She went to a May Day festival at my kids’ school with me once. She beamed as we watched dozens of kids in handmade dresses, dancing and wrapping the May pole. She leaned over and whispered in my ear, “I’m pagan,” and held my hand the whole time.

Last year she visited us in Oregon. I offered to fly her out, but she insisted on driving. She pulled up in a giant SUV filled floorboards to roof with spinning wheels and tools (almost all built for her by Alden). My kids unloaded the tools as Steph and I sat on the porch and talked about the future of fiber arts.

That night, after dinner, Stephenie, the kids, and I played Telestrations – a cross between the old telephone game and Pictionary. I had never seen Steph laugh so hard as I did that night. Stephenie was a part of my life. She was a part of my family’s life. We were family. I will miss her forever.

While she was here that time, we filmed the first Teacher Tea for the PLY Spinners Guild. It’s a segment where I sit down with spinning teachers, drink tea, and talk. It was so early in the PSG that we didn’t have good lighting yet, hadn’t figured out how to get a decent sound track, didn’t even have the PSG studio set up nicely, but none of that matters because Steph is such a joy. We’ve made the teacher tea with Steph public, viewable to everyone, guild member or not. Please sit down with some tea of your own and spend some time with this dear, darling woman.

https://www.plyspinnersguild.com/videos/9-teacher-tea-steph

Stephenie Gaustad was a wonder, and the world is better for having her in it. I’m better for having known her. Since I heard the news, I’ve been rereading all the emails she’d ever sent me, and it is helping replace some of the tears with smiles. Her closing lines especially help. I’m including a few of them here. I hope they make you smile too.

Hope that your spring days are full of beautiful green growth and smiles,

-SG

This morning’s rainbow reminded me of you. You are all the colors and you always bring a smile,

-SG

Well, the snow has turned to rain. It really is kind of late in the year for it. It is o.k. I have plenty of fiber to spin here, and a few wheels to do this.

-SG

You see, dear friend, I didn’t want to scare the hell out of you with dire futures. It ain’t like that one bit. I want to give you, dear friend, good news. And this is it.

-SG

The rain will pass, my dear Jacey. The rain will pass and you and I will keep growing,

-SG

So don’t fret over me. (In my best “Arnie voice”, “I’ll be back!”)

-SG

So I am laying here this evening basking in the glow of a completed job and oh boy, Jacey, my dear, are we going to have run raising some dust! Whoopee!

-SG

Stephenie Gaustad

August 1947–February 12, 2025

Footwear from 2,000 years ago is really different from what most of us wear today. Going barefoot was probably not uncommon, but there were times when you wanted something on your feet. For example, imagine exploring a cave barefoot. How far could you walk barefoot? Probably not very far. Mammoth Cave in Kentucky is the longest cave system in the world (over 400 miles and counting!) and ancient peoples had explored much of it thousands of years ago. We know they wore slippers because we have found slipper fragments inside the cave.

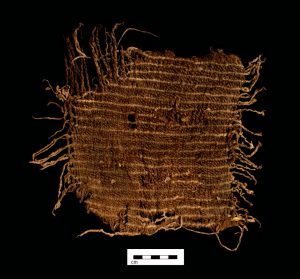

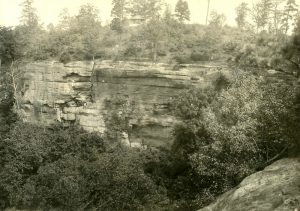

Footwear from 2,000 years ago is really different from what most of us wear today. Going barefoot was probably not uncommon, but there were times when you wanted something on your feet. For example, imagine exploring a cave barefoot. How far could you walk barefoot? Probably not very far. Mammoth Cave in Kentucky is the longest cave system in the world (over 400 miles and counting!) and ancient peoples had explored much of it thousands of years ago. We know they wore slippers because we have found slipper fragments inside the cave. Several of the slippers were excavated from rockshelters in the 1920s and 1930s as a part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). These images are from a rockshelter in Lee County in Kentucky that produced three of the slippers. Images courtesy the William S. Webb Museum of Anthropology, University of Kentucky.

Several of the slippers were excavated from rockshelters in the 1920s and 1930s as a part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). These images are from a rockshelter in Lee County in Kentucky that produced three of the slippers. Images courtesy the William S. Webb Museum of Anthropology, University of Kentucky.