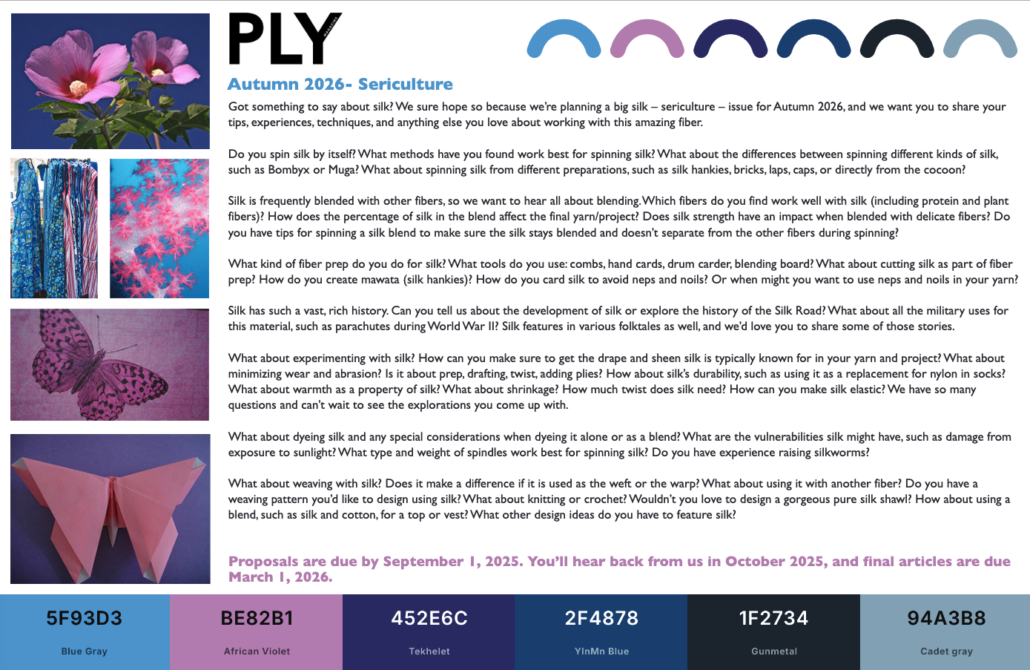

Mood Board: Autumn 2026 – Sericulture

Mood board: Autumn 2026 – Sericulture

Proposals due by: September 1, 2025

Final work due by: March 1, 2026

Got something to say about silk? We sure hope so because we’re planning a big silk – sericulture – issue for Autumn 2026, and we want you to share your tips, experiences, techniques, and anything else you love about working with this amazing fiber.

Do you spin silk by itself? What methods have you found work best for spinning silk? What about the differences between spinning different kinds of silk, such as Bombyx or Muga? What about spinning silk from different preparations, such as silk hankies, bricks, laps, caps, or directly from the cocoon?

Silk is frequently blended with other fibers, so we want to hear all about blending. Which fibers do you find work well with silk (including protein and plant fibers)? How does the percentage of silk in the blend affect the final yarn/project? Does silk strength have an impact when blended with delicate fibers? Do you have tips for spinning a silk blend to make sure the silk stays blended and doesn’t separate from the other fibers during spinning?

What kind of fiber prep do you do for silk? What tools do you use: combs, hand cards, drum carder, blending board? What about cutting silk as part of fiber prep? How do you create mawata (silk hankies)? How do you card silk to avoid neps and noils? Or when might you want to use neps and noils in your yarn?

Silk has such a vast, rich history. Can you tell us about the development of silk or explore the history of the Silk Road? What about all the military uses for this material, such as parachutes during World War II? Silk features in various folktales as well, and we’d love you to share some of those stories.

What about experimenting with silk? How can you make sure to get the drape and sheen silk is typically known for in your yarn and project? What about minimizing wear and abrasion? Is it about prep, drafting, twist, adding plies? How about silk’s durability, such as using it as a replacement for nylon in socks? What about warmth as a property of silk? What about shrinkage? How much twist does silk need? How can you make silk elastic? We have so many questions and can’t wait to see the explorations you come up with.

What about dyeing silk and any special considerations when dyeing it alone or as a blend? What are the vulnerabilities silk might have, such as damage from exposure to sunlight? What type and weight of spindles work best for spinning silk? Do you have experience raising silkworms?

What about weaving with silk? Does it make a difference if it is used as the weft or the warp? What about using it with another fiber? Do you have a weaving pattern you’d like to design using silk? What about knitting or crochet? Wouldn’t you love to design a gorgeous pure silk shawl? How about using a blend, such as silk and cotton, for a top or vest? What other design ideas do you have to feature silk?

Proposals are due by September 1, 2025. You’ll hear back from us in October 2025, and final articles are due March 1, 2026.