Following in the steps of a 2,000 year old spinner

We’re so happy to have Christina Pappas back on the blog today, to take us on a journey back in time as she tries to walk in the footsteps of some ancient textile producers.

In my last post, I talked a little about how archaeologists use objects to learn about the distant past:

“You look at a handmade textile and you see not just a pretty object, but the hours at the loom or knitting needles, the fiber drafting at the wheel, the alchemy at the dye pot, even the shepherds with their flocks. You can see all the steps and decisions that went into creating that object, all the places where one path or another was chosen. Archaeologists are constantly trying to trace back those paths, to see those moments when a decision had to be made and why. The whys are how we learn about culture in the distant past. We can look to the past and see when and why spinning one kind of fiber over another was chosen, what changes were happening that led to that decision, and what were the ramifications of that decision….”

All the steps and decisions that go into making something are known as a production sequence. One of the ways we can learn about a production sequence from the past is to actually make the object ourselves; to try to recreate the steps that went into crafting something to understand how that process fits into everyday life.

Harvesting Joe Pye Weed this past September. This was a plant used for fiber in prehistoric Kentucky. These plants are destined to become yarn for my project.

For example, let’s think about a woven wool shirt. What are all the steps to make it? Cutting the fabric and sewing the garment are steps, but we need to look all the way back to the very beginning if we are going to understand the entire production sequence. So we have to think about the sheep, processing the fleece, spinning the yarn, weaving, and then finally cutting and sewing the garment. That’s a lot!

Now, imagine the same process over 1,000 years ago in a Viking settlement. What technology was available to you? What other kinds of chores and activities were going on every day? How would the need to make a wool shirt fit into daily life? By trying to make a wool shirt exactly the way a Viking would have, we can estimate the time and effort needed and get a glimpse into the value placed on this work in their society. Similar experiments and studies into Viking sailcloth have shown how labor-intensive its manufacture was and how valued that process would have been. (This, this, and this are just a few examples of these projects.)

A slipper form a cave in Kentucky. This will be the slipper we will try to replicate.

At the University of Kentucky, we have a collection of prehistoric textiles from dry caves and rock shelters that are around 2,000 years old. These include fragments of shawls, bags, mats, and slippers. They are in various states of preservation but all are made from plant fibers. I know the structure of the yarns and the types of weaves used to make each object, but I’m not sure how they were made. How were the plants processed into yarn? How was the yarn spun? How easy was it to dye the yarns? How long did it take to weave a bag or make a pair of slippers? We know only a little about the process of making these textiles, but I think I can change that.

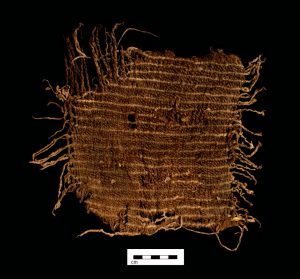

A fragment of a bag from a Kentucky rockshelter. Complete objects, like bags, are very rare from archaeological sites. We will look at this fragment, as well as a few others, as we make our bag.

Over the next several months, I’m going to try to replicate two different kinds of textiles, a slipper and a small bag. I’m going to start at the very beginning with gathering the plants and how to process them for fiber. I’ll be experimenting with different ways of spinning the fiber and how the yarn I make matches up with the archaeological examples. There will be the weaving of each object and a ‘field test’ to make sure they can function as they are supposed to. In the end, we’ll compare my replicas with the originals and see what we’ve learned. I’m definitely not the first person to try this sort of project with archaeological textiles, and we’ll talk about the projects that have come before me. I’ll be checking in on the PLY blog periodically to document my progress, and I’ll report on both my successes and my failures. This is science folks; I expect there to be some failure along the way.

A few examples of yarn and textiles I’ve made to learn about how prehistoric fabrics were constructed.

Next time, we’ll get to know the two objects I’m going to be replicating. We’ll take a look at their yarn and weave structure and make some guesses about what was done to produce each object. That will serve as our roadmap for the whole process. Stay tuned!

Chris Pappas is an archaeologist by day and a fiber fanatic by night who is happiest when she can be both at the same time. She lives in Kentucky with her husband, adorable baby girl, and two crazy beagles.

I find this totally fascinating! Thank you so much for sharing this project with us! I can’t wait to learn more – we have LOTS of Joe Pye Weed at our house! LOL!!

Thank you so much for sharing this process with us. It is wonderful to get a glimpse into both your work and the work of ancient civiilizations!

This is so interesting! I’m really looking forward to reading about this project as it progresses.

So happy to read about your most recent endeavors and look forward to future entries.

For me, your writing is the highlight of PLY.

This is very interesting. An excavation in Carter Co., KY funded by the KY Heritage Council resulted in the uncovering of massive amounts of well preserved plant remains. Among the artifacts observed were two twined slippers and a bag fragment. Also, there were fragments of what ay have been another slipper in a prehistoric trash pit. One of the slippers was sent to OSU for study and was dated at 638BC +/-60yrs. However, the fibers making up the slippers were not identified. Subsequent review suggested Eryngium yuccafolium or possibly Boehmeria cylindrica. This ID was suggested by the coarseness of the fibers and the lack of any “nodes” along the course of the fiber bundles used to make the slippers. However, we had not considered the possibility of Joe Pye Weed fibers since we had not found reference to their use, for this purpose, in our literature search. Thus, the use of Joe Pye Weed to prepare a slipper and bag is of considerable interest.