Let’s Talk About Sparkle Fluff

words by Jacqueline Harp | photos by Susan Schroeder

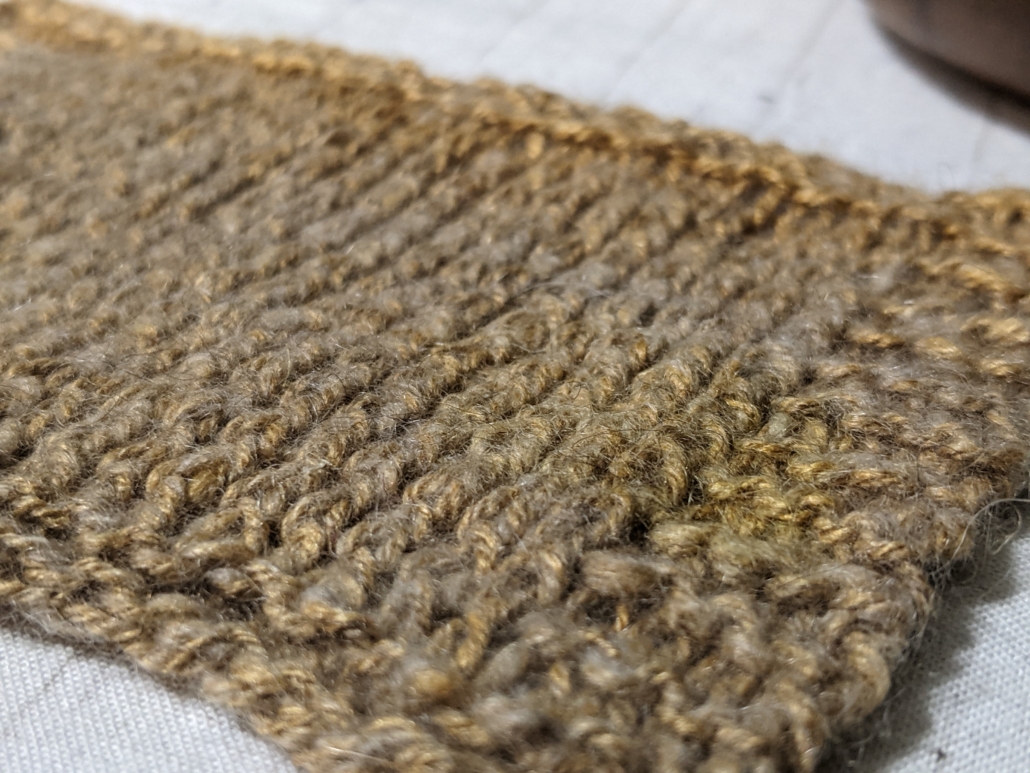

Have you ever heard of Sparkle Fluff? Oh, my! Envision a handful of fiber goodness that features a colorful mixture of mohair locks and glitz, and it is known to make handspinners smile when they get their hands on it. Sparkle Fluff is a fiber preparation composed of a color-coordinated mix of mohair locks, sheep wool locks, and loose Angelina fibers. It is ready-to-spin and full of texture and sparkle. You can spin it into a wide variety of chunky, fantastical art yarns or sprinkle it into carded preparations to add some extra pizzazz.

Let’s meet the innovative mind behind Sparkle Fluff, Susan Schroeder of Rusty Spur Ranch and Creations, located in Rathdrum, Idaho. Be prepared to be inspired to use mohair in ways that bring the most joy to your spin projects.

Meet the fiber creative

I came across Susan a few years ago, at a fiber arts festival in the Pacific Northwest, and was impressed with her creativity, hard work, and effervescent personality. Susan is an expert indie dyer, fiber artist, and Angora goat shepherdess to a well-cared for flock that provides high quality mohair for her fiber projects.

Susan’s fiber arts journey started with knitting as a way to pass the time during family road trips. She bought a handspun skein from Symeon North, author of the book, Get Spun (2010), and this beautiful yarn inspired Susan to learn handspinning. She started with a drop spindle and eventually learned to use a wheel. She then taught herself the art of dyeing fiber to bring unique colors to her own spinning fibers. A few years later, four Angora goats made their way into Susan’s life to provide mohair fleeces and natural weed control for her farm. Inspired by the growing flock of Angora goats on her farm, she started a fiber arts studio and named it the Rusty Spur Ranch and Creations.

Susan strives to use the whole mohair fleece in a productive manner. The prime locks are used for Sparkle Fluff, while clean belly fleece goes into cat toys. Remaining parts of the fleece go into the garden as mulch or into the bottom of plant pots to improve water retention.

Gathering the elements

Raw fleece selection is step one. Within a batch of Sparkle Fluff, there may be two or three different textures of mohair depending on what Susan has available. She knows the fleece of each goat in her flock, as it varies from goat to goat. Some fleeces are Navajo-style, with long, straight locks, while others have tiny curls.

Along with the mohair locks, each batch of Sparkle Fluff may have wool locks from up to five different breeds of sheep. While the mohair comes from her own flock, the sheep wool is sourced from different farms. For both fiber types, Susan looks for well-separated, open locks that are not felted and that contain the least amount of hay.

Secondly, she uses gentle washing methods so the locks don’t stick together. Once the locks from all fleeces are clean, she will dye bulk batches of locks in different colors.

Susan: I don’t have a Sparkle Fluff color idea in mind when I start dyeing fleeces. I will dye up to five fleeces at once. Each fleece is dyed a different color. After the fleeces are dyed, I start playing with the colors I created. The key is to take a few handfuls of various proportions and start mixing them together. If I like what I have, I will pull large amounts of dyed fleece and weigh it into about 10 ounce batches before I start mixing.

Mixing it up!

Once she has selected the color and fiber mix, she makes a pile and starts handpicking the locks and placing them into a large bin. She uses her hands to carefully pick and separate the locks because a fiber picker would rip the locks apart. After filling the bin, she gently tosses the fibers like a salad to ensure the Angelina is well distributed and the locks are evenly mixed to her satisfaction. She wants the locks and Angelina mix to be loose and flowing, not clumpy.

When mohair is mixed with wool and Angelina, the mohair pops! All fibers in Sparkle Fluff support the pop and shine of mohair.

If Susan had to select three words to describe her Sparkle Fluff, she would choose:

Sparkle – because the Angelina throughout the fluff looks dazzling in the sunlight.

Shine – since mohair has a mirror-like shine.

Texture – the feel of so many different locks, wools, and fibers to be enjoyed however one wishes.

Spinning Sparkle Fluff

Chunky. Fine. Direct to wheel. Carding and blending.

Sparkle Fluff has no limits to its creative use. Susan’s favorite way to spin Sparkle Fluff is to take handfuls and let it flow through her wheel for a highly textured, bulky art yarn. She notes that Sparkle Fluff can also be lightly blended on a blending board for those who want more control over the texture and weight of their handspun.

Susan: I have seen other handspinners run a batch through a drum carder and spin it fine, with amazing results. As a person with curly hair, I appreciate the different textures of wool and mohair, and I like that my Sparkle Fluff preserves and highlights the texture of the locks.

Other surprising ways to use Sparkle Fluff: Fill little glass bottles with it and place those bottles around your studio to liven things up. Felt it into a gnome’s beard for some spice and color. Weave it into a wall hanging with some driftwood you picked up from the beach. The possibilities are endless!

As a parting thought to handspinners looking to start their next mohair spinning projects:

Susan: Don’t be afraid to try something new. A lot of spinners stick with wool because it’s a fiber they know. It takes courage to branch out and try something new. Especially when spinning with locks – you have to let go and let the locks flow. It is not precise. You are not looking for a specific twist direction or the perfect spinning ratio. Sometimes it takes a new spinner a long time to feel comfortable enough to be able to flow. But give it a try. Maybe you will get it right away, maybe you won’t, but just keep playing with it and practicing. I promise the Angora goats will keep growing fiber, so we won’t run out!

Jacqueline Harp is a freelance writer and multimedia fiber artist who spins, felts, weaves, crochets, and knits in every spare moment possible. She is also a certified Master Sorter of Wool Fibers through the State Univ. of N.Y. (Cobleskill) Sorter-Grader-Classer (SGC) Program. Her Instagram handle is @foreverfiber