A woman’s work was never done: spinning in medieval art

by Judy Kavanagh

If you were a woman in medieval Europe (between the 5th and 15th centuries CE), you would have had many chores to perform every day such as cooking, cleaning, looking after children – and spinning. You would have needed to produce large quantities of thread from both wool and flax to weave into cloth for clothing, bedding, bags, sails, and countless other items. To get an idea of the amount of spinning required for weaving, a piece of cloth just one yard square and woven at 25 threads per inch required 900 yards of warp thread and another 900 yards of weft.

Now imagine spinning all this thread using a spindle. The spinning wheel first appeared in Europe only during the 13th century and was still very new technology. The spindle, however, is ancient and dates back thousands of years, and it was the spindle that was still the tool of choice for most of the medieval period.

To make enough thread for your needs, you would have spun everywhere and all the time – while walking, riding, gardening, doing errands, and tending your livestock. You would have used a distaff to keep your fibre clean and organized. A distaff is simply a long stick that acts as a third arm. The fibre is tied on at one end and the other end is stuck through your belt behind your waist. When you cradle the distaff shaft in the crook of your elbow, it leaves both hands free to either spin or do other tasks. If you need to stop spinning you can just stick the spindle into the fibre.

We can learn a lot about how and where medieval spinning was done by looking at artwork of the time. The Bustling Housewife, a Swiss tapestry woven between 1470–80, shows the busy housewife spinning with a distaff and spindle with a basket of birds on her back and her baby in a sling while riding a donkey and tending her cow, goats, and pigs.

With a distaff tucked in your belt, it’s easy to pause your spinning while you perform another chore like this woman from the 14th-century Luttrell Psalter, who has stopped spinning just long enough to feed her chicks and an enormous hen.

Illuminated manuscripts like the Luttrell Psalter were often decorated with little images in the margins. They are called drolleries and often had nothing to do with the subject of the text. Some are quite imaginative with monsters and mythical creatures, and some show wonderful glimpses of everyday life.

Medieval age spindles were not like the drop spindles most of us use today which have large whorls glued onto the shaft. A medieval spindle typically had a very small, light, removable whorl, usually at the bottom of the shaft, that was made of clay, bone, stone, or lead.

In the past few years, a few modern spinners have rediscovered the advantages of this style of spindle. As a spindle maker, I’ve made medieval-style spindles and learned to spin using a distaff. Because the whorl is compact and light, the spindle spins very fast but not for a very long time, which is perfect for making fine, high-twist yarn suitable for weaving. When a sufficiently large cop has built up on the spindle, you can remove the whorl because the cop itself acts as a whorl. Drafting is done with the hand near the distaff while your other hand flicks the spindle as needed. It’s a surprisingly comfortable position to spin in.

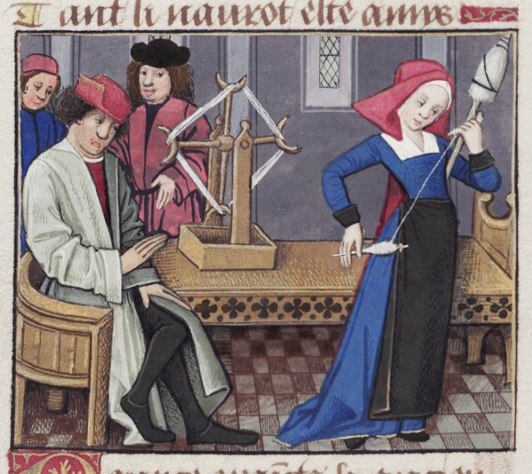

This method of spinning is demonstrated in this lovely illustration in an illuminated manuscript about famous real and mythical women. The graceful woman in this picture is Pamphile, an ancient Greek woman who was credited by Pliny the Elder with inventing a method of spinning and weaving silk. The book De Mulieribus Claris was written by Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375), and this copy was translated into French and written out by hand between 1488 and 1496. The printing press was another bit of new technology at this time as it had only begun to be used in Europe in the mid 1400s. Before then all books were laboriously copied out and illustrated by hand.

Because the spindle whorls of this time were so small and were removed when the cop got big enough, it’s hard to see them at all in many illustrations, but you can see the whorl in this picture of a woman winding spun thread onto her spindle. She has butterflied the thread around her left hand just as I do when I wind the thread onto my spindle. This picture is entitled Husband and Wife as Equals and is from an illustrated manuscript of Le roman de la rose, an allegorical love story started by Guillaume de Lorris around 1230 and continued by Jean de Meun 40 years later. There are about 320 whole or partial versions of this book in existence, but this one is particularly lavish as it was prepared for French royalty.

Here’s a beautiful illustration from a copy of Jean Froissart’s Chronicles, a history of the Hundred Years War. The woman sits under a tree and has paused her spinning to talk to a young man. She has a distaff and a spindle, and there is an enormous strawberry growing behind them.

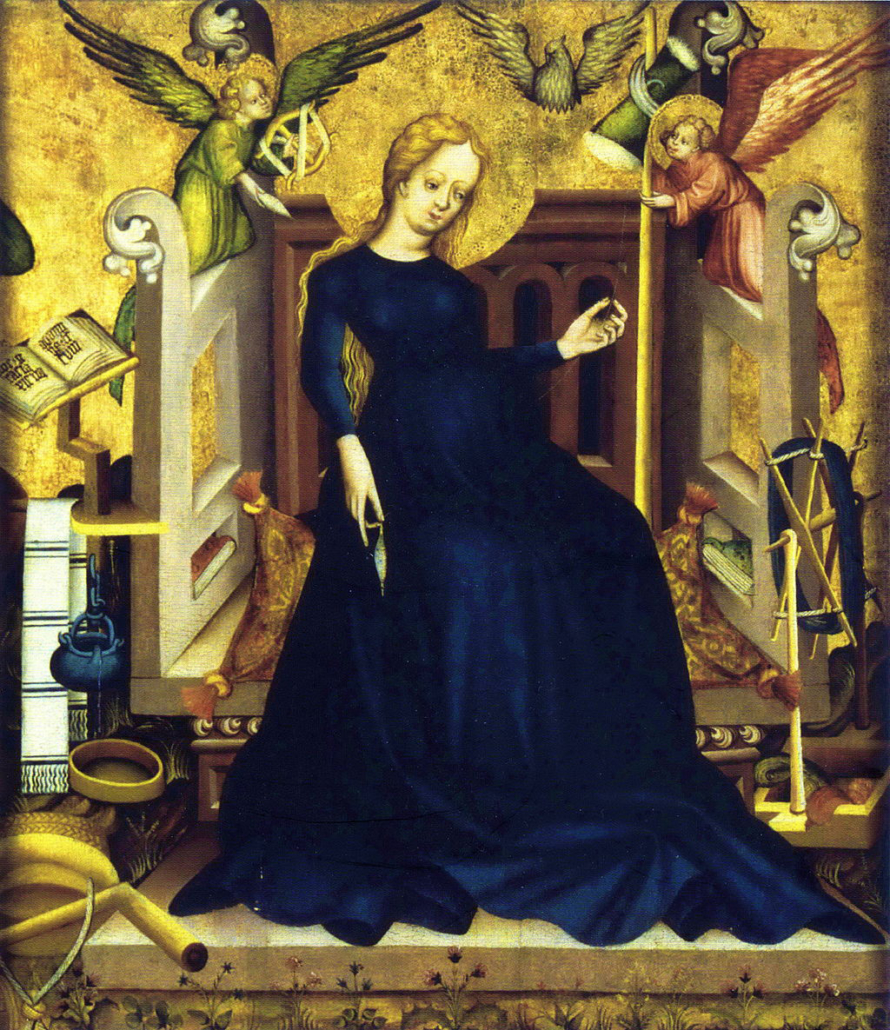

Spindles often appear in religious art of the time. This is Maria gravida, a Hungarian altar painting from 1410. A pregnant Mary is spinning a very fine linen thread using a spindle while an angel holds her distaff containing flax wrapped in a cloth. Another angel is winding off yarn from a spindle onto a niddy noddy and there’s a skein winder holding blue dyed thread beside her. When the painting was examined under infrared light, it was discovered the artist had painted the baby Jesus in Mary’s belly underneath the paint of her gorgeous blue dress.

In this 15th-century drawing from Germany, Mary is spinning from a distaff, Joseph is doing woodworking, and the baby Jesus is winding thread off a spindle onto a niddy noddy. Perhaps this was a task often given to children during this time.

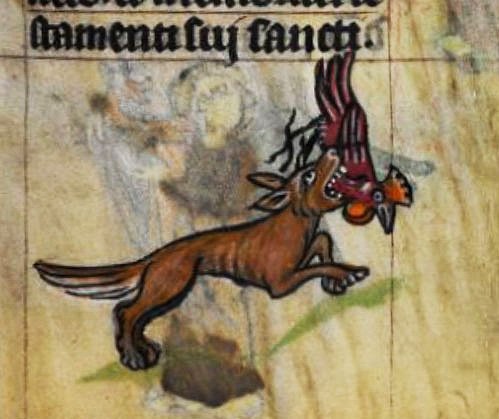

Distaves often seem to have been turned into weapons in medieval art. In this drollerie from The Smithfield Decretals, Reynard the Fox, a popular trickster in medieval stories, has stolen a women’s goose, and she’s chasing after him with her distaff. The Smithfield Decretals is a collection of medieval canon law and was written out around the year 1300. The illustrations weren’t added until 40 years later, perhaps in an attempt to lighten up what must have been a rather boring book.

The Maastricht Hours is an illuminated manuscript produced in the early14th century in France. In these illustrations from facing pages, a woman has hitched up her skirt and is going after the fox who is running off with her chicken.

In this drawing in the Rothschild Canticles, a cat (or leopard?) has gotten into trouble trying to steal something from a bowl, and a woman with a distaff is chasing it.

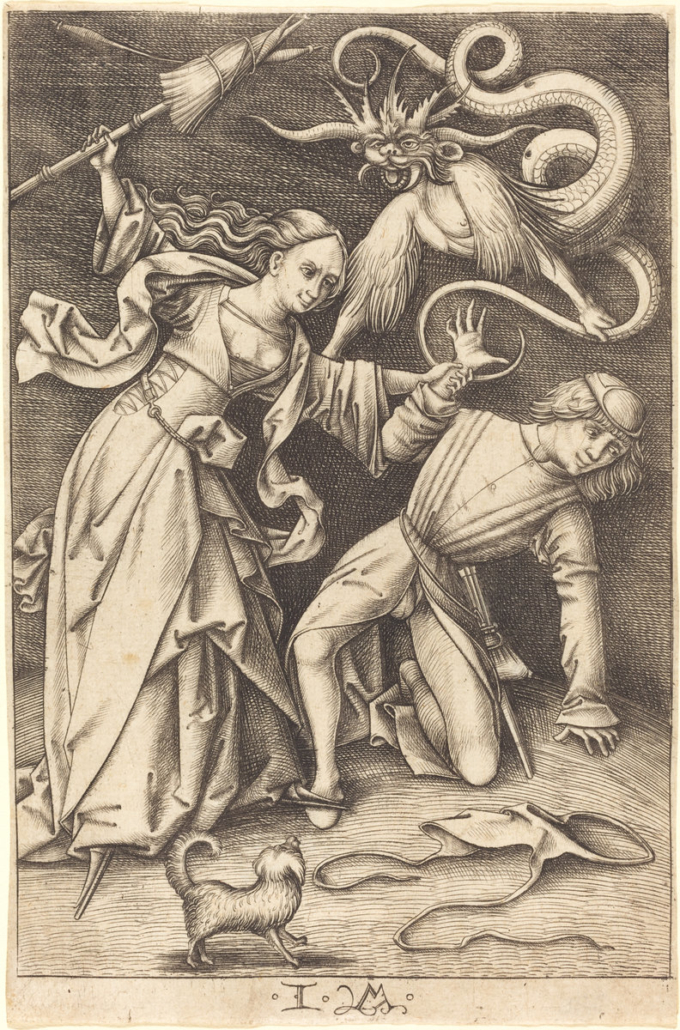

Ishrael van Meckenem produced this engraving called The Angry Wife near the end of the medieval period, around 1500. All I can say is that the husband must have left the toilet seat up.

This illustration is from a French Arthurian romance created between 1275–1300. A woman with her headdress flying behind her is jousting with an unarmed knight. The woman looks angry and is using her distaff as a spear with the attached spindle flying in the air. Even her horse looks angry.

Spinners who own cats know what can happen when you spin with a spindle. This illustration from The Maastricht Hours shows a woman spinning using a freestanding distaff. Her tabby cat has pounced on her twirling spindle. Is she rolling her eyes?

Museum Meermanno

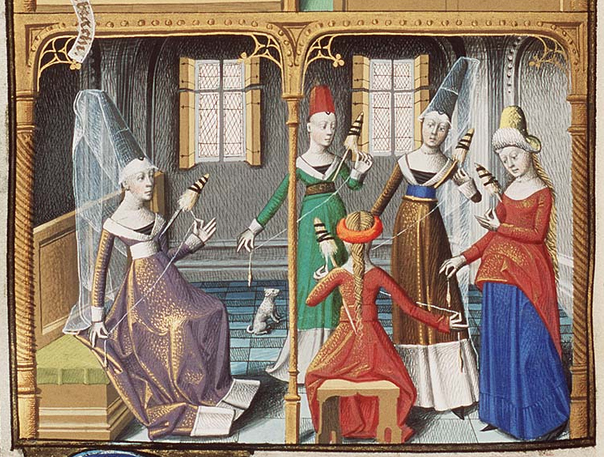

We love to get together with our friends and spin and chat, and it must have been the same 600 years ago. These elegant French ladies were painted around 1478 and appear to be spinning a fine linen thread on their spindles. This is from a medieval manuscript of La Cité de Dieu.

Sardanapalus, the King of Assyria, has dressed up as a woman and is spinning with his ladies. The mostly fictional story of Sardanapalus was told by the Greek historian Diodorus during the first century BCE. According to Diodorus, King Sardanapalus spent his life being lazy and indulging himself. He often dressed in women’s clothing and wore makeup and had both male and female lovers. This book was translated into French around 1480 as Les Fais et les Dis des Romains et de autres gens.

Near the end of the medieval era, spinning wheels start to appear in art. They are hand-turned spindle wheels similar to what we call a great wheel or a walking wheel. Here a spinner is interrupted by a man who has draped his arm around her shoulder and is trying to feel her behind. It’s titled An amorous encounter and is from The Smithfield Decretals, c. 1275–1325.

Looking at these spinners from so long ago and spinning using a distaff and medieval-style spindle gives me a deep sense of connection to the lives of medieval women. Any of them could be my 25th great-grandmother, and I often wonder if they found satisfaction in their spinning as I do – feeling the fibre between my fingers, producing an even thread, seeing the cop build up on the spindle, and finally weaving the thread into cloth.

Judy Kavanagh is a spinner and spindle maker living in Ottawa, Canada with her 3 yarn-loving cats. She loves to experiment with making and spinning different kind of spindles. Judy is often found teaching spinning or weaving at the Ottawa Valley Weavers’ and Spinners’ Guild.

For more articles like this, subscribe!

Get sneak peeks, extra content, behind-the-scenes details, and updates straight to your inbox

PLY Magazine believes that Black lives matter, as well as LBGTQI+ lives. Those most vulnerable and persecuted in our communities deserve our love and support. Please be good to each other.

And also I should add that Judy is a spindle makers and restore antique spinning wheels. She recreated for me bobbins on several antique wheels that I own. She can be reached on Facebook or at her Etsy shop with the same name.