Book Review: Nini Towok’s Spinning Wheel: Cloth and the Cycle of Life in Kerek, Java

reviewed by Sukrita Mahon

A part of the Fowler Museum’s series on textiles around the world, this book explores the textiles in a small rural community in East Java. The culture and textile tradition in Kerek are extraordinarily vibrant, forming an integral part of this society. Modern-day spinners, weavers, and dyers in the west are likely to find much inspiration in its pages. It doesn’t seem so long ago that we were all cloth-makers – not for pleasure but necessity. The unique imprint of each artisan’s work somehow creates a sense of deeper connection with society, nature, and spirit.

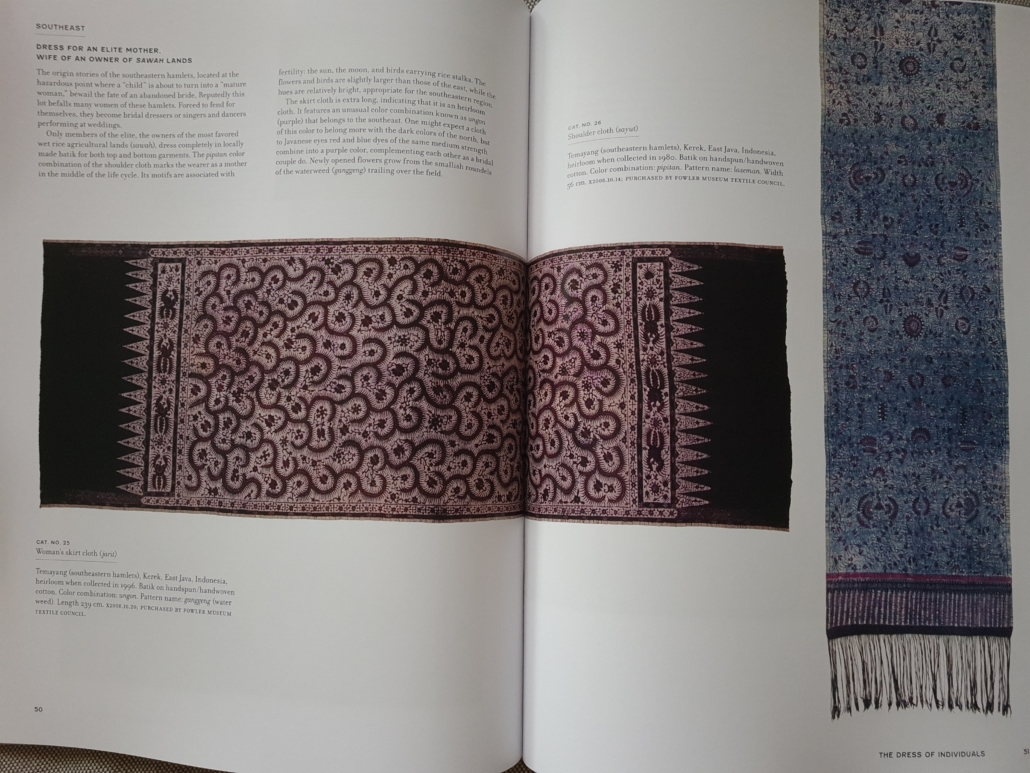

The museum had an accompanying exhibition to this book, and the format is very much the same as an art exhibit, with many pieces of handspun and handwoven textiles featured and explained in detail. Each piece has a cultural context and is worn by certain members of society or used for certain purposes only. They indicate everything from social class, land ownership, age, and marital status to ancestry. Largely made as single lengths of cloth, they are worn by both men and women, but in recent years commercially made clothes have come to dominate the menswear.

Spinning, dyeing, and weaving are all considered mythical and ritual activities, performed mainly by the women. Nini Towok is the mythical figure of a spinner in Kerek’s oral traditions. She is considered to be visible on the surface of the moon, spinning on a wheel. With the cotton fields resembling the night sky and the stars, she feels at once close to earth and ethereal. “Part goddess, part crone, Nini Towok sends her finely spun cotton yarn to earth in the form of moonbeams.” A type of guardian spirit, she is believed to watch over each part of cloth-making, and offerings are made to her at the beginning of a project.

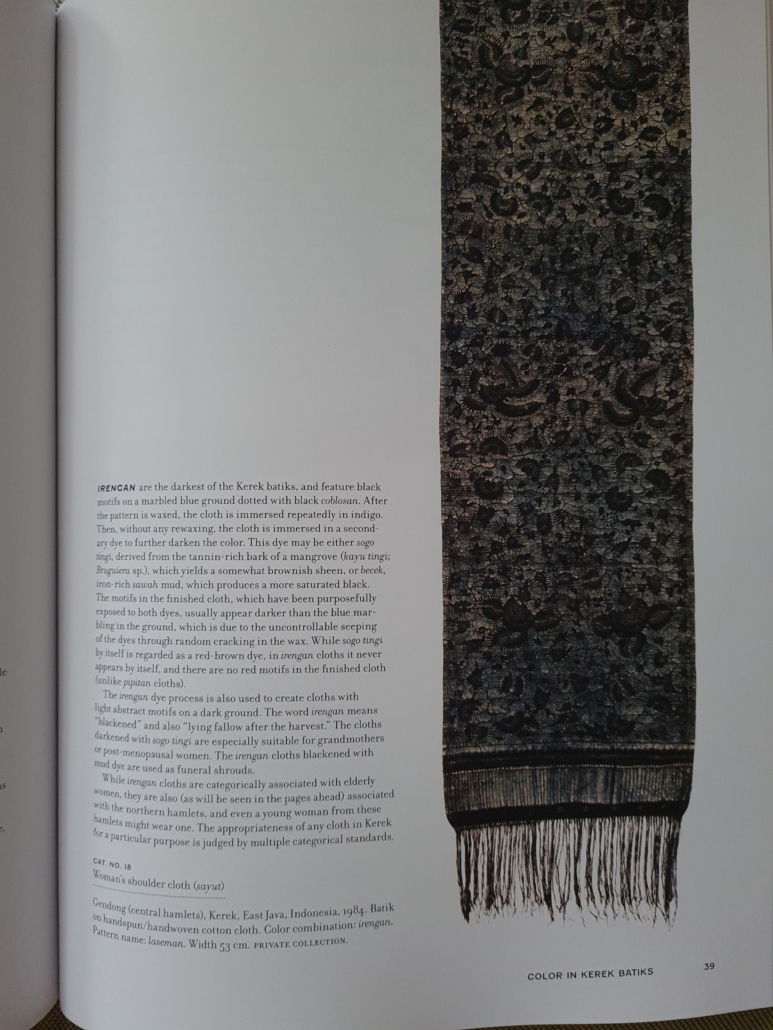

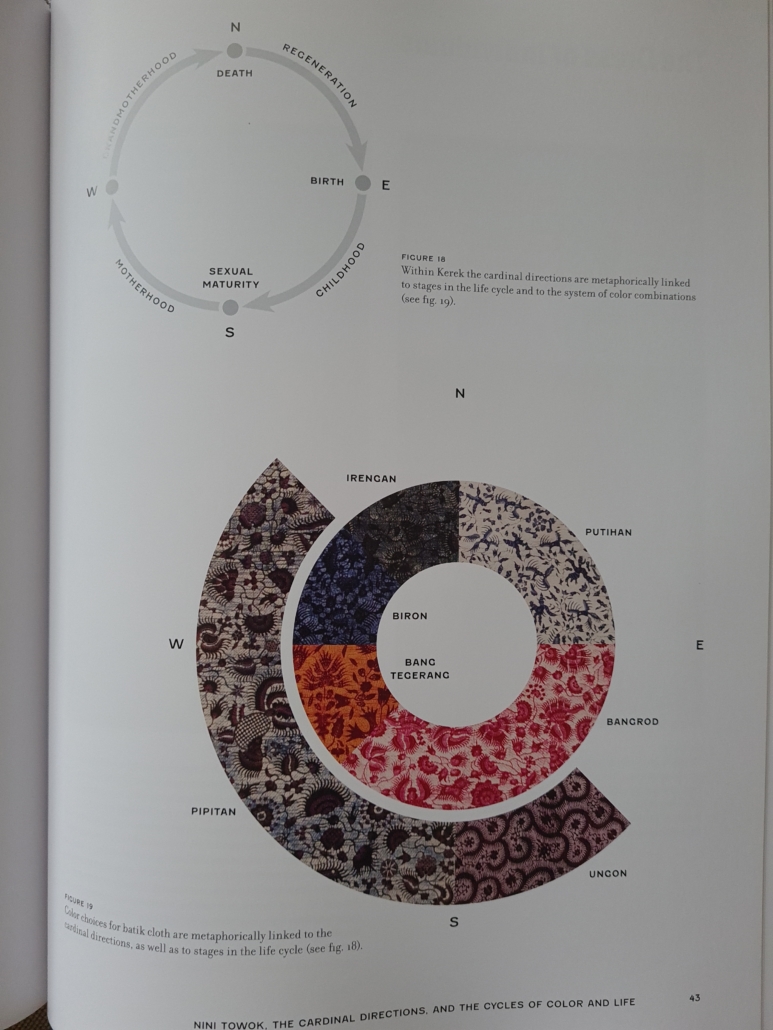

The dyeing process is also steeped in ritual, although the book only mentions it briefly. Natural dyes produce blacks, blues, and reds, and brown cotton is also used. The patterns are formed mainly using batik techniques (wax resist dyeing), and the symbolism is deeply connected to the natural world. Common motifs include centipedes, flowers, birds – all imbued with meaning. Some colours and symbols can be protective, and some denote youth and fertility. Abstract symbols are also used, less commonly, often in the case of men’s clothing.

The life cycle of a woman is a theme that returns again and again in the fabric of this region. From youth and marriage to motherhood, and finally old age, women adorn themselves in different ways and acquire more status with age. Special cloths are used to carry children, and these are very often handspun and handwoven, even when other clothing is not. Funeral rites also feature certain textiles that are placed on the coffin of the deceased and left there until the final moments. Afterwards, they are taken home by the family and preserved as heirlooms.

As can be imagined, environmental degradation has affected the textile practices considerably. Indigo is the only natural dye still used, since other traditional plant dyes are now difficult to come by. Traditional textile worker families are all but gone, with many people no longer interested to take up the vocation. I can’t help feeling that a lot has been left out of this book in terms of the socio-economic context, and the reader is expected to make many assumptions that may be on the idealistic end of the spectrum. For instance, many of the residents are landless labourers, who form a vulnerable demographic, subject to urban migration away from the region. There is no mention at all of how increasing globalisation might affect the future of Kerek textiles.

With such awe-inspiring textiles featured, I was left wanting more from the book. The pages about the mythology and spiritual practices connected with the textiles were too fleeting for my liking – although readers may feel a sense of familiarity in them. Since it’s a small and isolated region, there were many questions I found myself asking, for which the answers aren’t easily obtainable. For this reason, the material feels a little clinical and academic. Personally, I hope for a future in which textiles are alive with intention and meaning in our everyday life in the west – glimpses like Nini Towok make it easier to imagine.

Rating: 3.5/5

PLY Magazine believes that Black lives matter, as well as LBGTQI+ lives. Those most vulnerable and persecuted in our communities deserve our love and support. Please be good to each other.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!