Book Review: The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook

reviewed by Sukrita Mahon

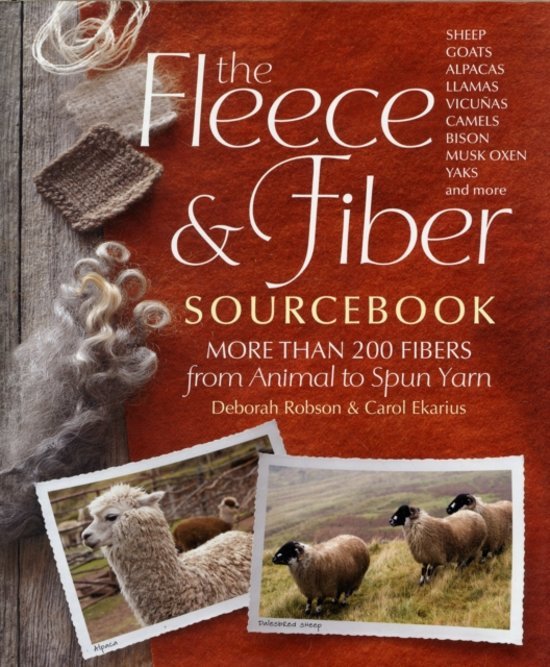

If you have been spinning for any length of time, you have probably heard of The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook by Carol Ekarius and Deborah Robson or maybe own it yourself. If not, you probably should – it’s a collection of over 200 varieties of fibre from around the world, methodically catalogued. Each fibre is spun, usually using different preparations, and its characteristics explained: how it spins up, how it takes dye, what it’s best used for. There is so much diversity in types, textures, and how they all behave that each could be an in-depth study on its own.

As a spinner, breed studies truly excite me because it’s such a tactile experience and so different every time. It’s hard to articulate certain aspects because fibres can have seemingly conflicting characteristics, like shiny and silk-like yet coarse; poufy and springy but also rope-like if spun a certain way. Because of this, I am always looking to explore breeds that are new to me and even spin the same one a lot to become more familiar with it.

When other people find out that you spin, it’s quite common to be offered bags of raw fleece; I tend to decline most alpaca but love to receive wool. Although alpaca is much more common in my area, it tends to be dustier and more difficult to work with when it’s full of second cuts, for example. For some reason I find that I don’t mind doing some extra work to salvage wool because it usually comes out well after a good scour. So when I was given a mystery bag of wool from a local farm, I sought the help of this book to identify the sheep breed. I won’t lie, there are probably easier ways of identifying wool – like going to the source and finding out or asking someone who is more experienced – but this was a nice challenge that gave me an excuse to flip through a beautiful book. How could I resist? The book could also be helpful if you have a bad memory for breed names or just forget to label your wool.

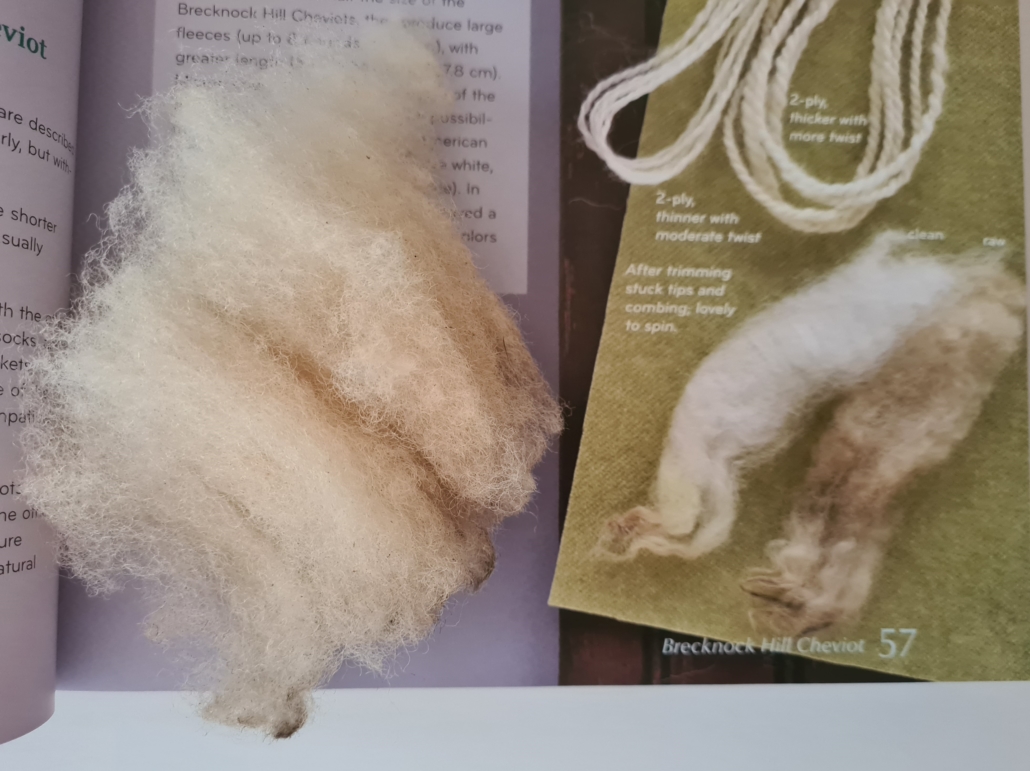

Right out of the bag, my mystery wool was yellowed, fluffy, and full of second cuts that were quite careless, so it was likely the sheep weren’t reared for their wool. To go about identifying it, I tried to answer specific questions: Does it feel more hairy or woolly? Is it soft, coarse, or somewhere in-between? Is it greasy/does it seem to have a lot of lanolin content? Is there a noticeable or visible crimp in the fibre? What do the tips look like? This isn’t a complete list but should give you enough to start searching.

In my case, the wool felt springy, not at all like hair, and perhaps downy, although I was a little vague on what that term meant. It wasn’t especially coarse, but not soft. I didn’t think it had the kind of greasiness of Merino or even some Corriedale. It had no visible crimp, and the ends were, for lack of a better word, sort of tippy. This is in contrast to, say, Corriedale which often has blunt tips, or Border Leicester, which has more pronounced tips.

Starting in the Down section of the book, I could immediately see a resemblance. Even the more crimpy down breeds had a similar kind of ‘feel’ to this wool. It helped a lot that the photos are so clear and detailed, with multiple samples. Here it’s evident that Cheviot has more crimp and tippiness compared to my wool.

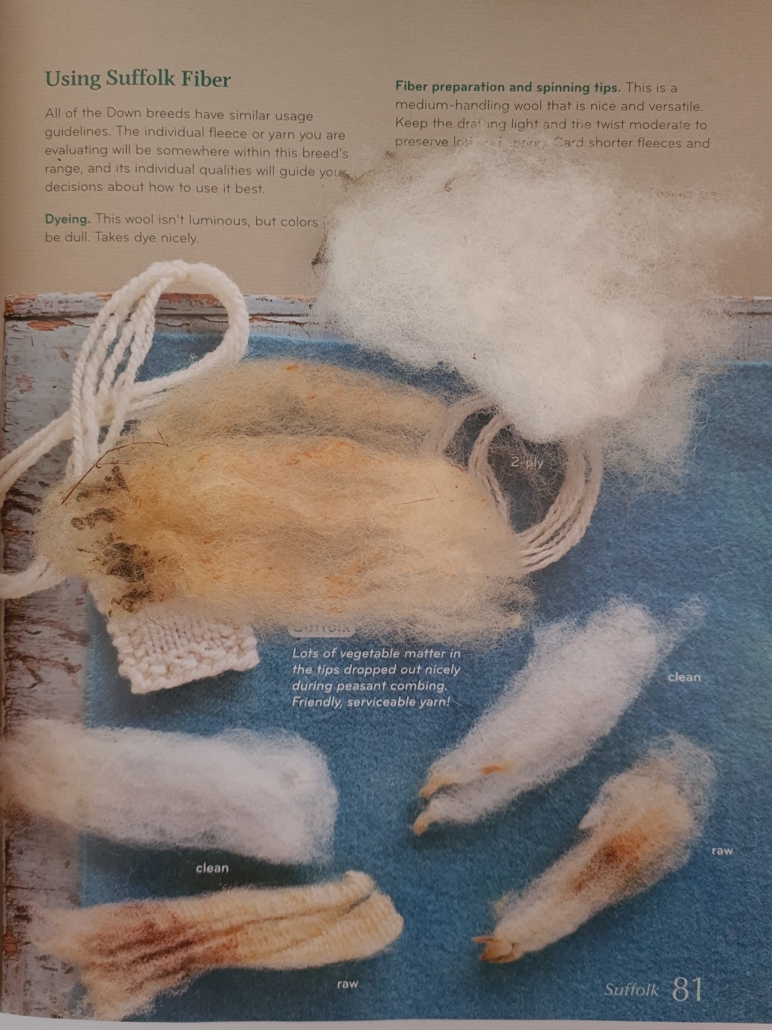

The Suffolk seemed to be a good match because it had the same kind of reddish brown tint in the raw sample, which I initially thought was feces. One of the samples pictured in the book shows much more crimp, and the other has barely any. After scouring they come out bright white, with a bit of tippiness remaining, which is what I found for my wool as well.

The other breed that came close in similarity was Texel. The colour of the raw wool is slightly different, but the textures and finished wool are so similar that it could easily have been this breed.

I suspected it wasn’t Texel because Suffolk is much more common in this area, in addition to the odd red tinge that none of the other raw samples seemed to have. Both Suffolk and Texel are primarily bred for their meat, so the wool is often discarded. According to the book, though, where handspinners are concerned, there are no disadvantages and both make excellent, warm yarn and garments.

Fortunately, I was able to get in touch with the person who gave me the wool to ask if they knew what breed it came from. They confirmed it was Suffolk, and you can imagine how excited I was to hear that. I also learned that the sheep were named Lamb and Chop, which is apparently a common set of names for sheep in Australia.

Needless to say, I think all spinners should have access to this book; it’s such a treasure. The only negative I have to say about it is that it’s not a complete catalogue of all the sheep breeds on the planet; it’s mainly focused on the ones known in the Americas, Europe, and Australia, so if you live in Asia or Africa, it may not be as helpful. I do hold out hope that we will get more editions in the future as interest in handspinning and sustainable farming grows.

5/5

PLY Magazine believes that Black lives matter, as well as LBGTQI+ lives. Those most vulnerable and persecuted in our communities deserve our love and support. Please be good to each other.

Awesome review! So excited that you were able to identify the wool. I’ve had this book on my wishlist and this definitely encouraged me to move it up a few spots!