We Need Photos of Your Spinning Hands!

/0 Comments/in Frontpage Article, Spinning, We couldn't fit it in the print issue!/by Guest BloggerWe are gathering photos of the different ways that spinners spin (how you hold your hands, how you hold your fiber, the position of drafting) for the Autumn issue of PLY. If you have a close-up photo of just your hands spinning (the bigger the file, the better) and you don’t mind us using it in our Autumn issue, please email your photo to jacey@plymagazine.com.

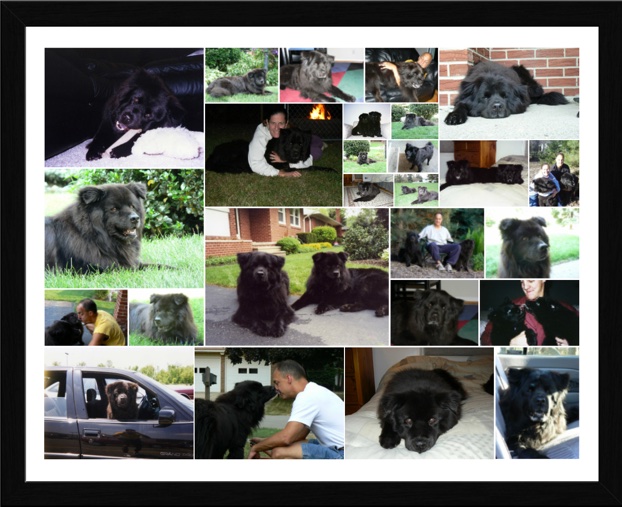

A Furry Love Story

/0 Comments/in Frontpage Article, Spinning, We couldn't fit it in the print issue!/by Guest BloggerWords and Photos by Liza Jennings Seiner

A few years ago, I was talking to a friend who knew I was a handspinner. Somehow we stumbled onto the topic of spinning lots of different kinds of fiber, and she asked me: “Could you spin dog fur?” I said I probably could but hadn’t tried. When I asked her why, she told me a love story.

She and her husband used to own 2 Chow Chow Newfoundland dogs. These particularly cherished pets had since passed away, but she had kept some of their fur from their frequent brushings. Her 25th wedding anniversary was coming up, and she wanted to make something special for her husband; maybe she could knit a lap blanket from yarn made from the dogs’ fur.

I told her to send what she had and I would look it over. A few days later, I received a large box weighing over 4 pounds, full of plastic bags containing brown dog fur. She had saved this fur for several years but hadn’t looked at it since then. It was a little ripe smelling, so I washed it in Dawn dish soap and laid it out to dry.

Then I began the process of spinning the yarn. I made several small skeins, sampling the fur and blending it with other fiber, knowing it would be quite heavy alone. I sent her pictures, and her initial reaction was that these dogs were known as the “black dogs,” but their fiber was quite brown. What to do? Blend some black fiber to give it a black appearance?

After several attempts (blending in black Merino) and a trip to visit her, we determined that to get a good black color, I’d have to add so much other fiber that the dog fur would be overwhelmed by it.

We also discussed what she’d be doing with it. Although she could knit something with the yarn I would spin, she’d have to do it “on the sly” when her husband wasn’t likely to discover what she was up to. She wanted this to be a complete surprise. Hmmm.

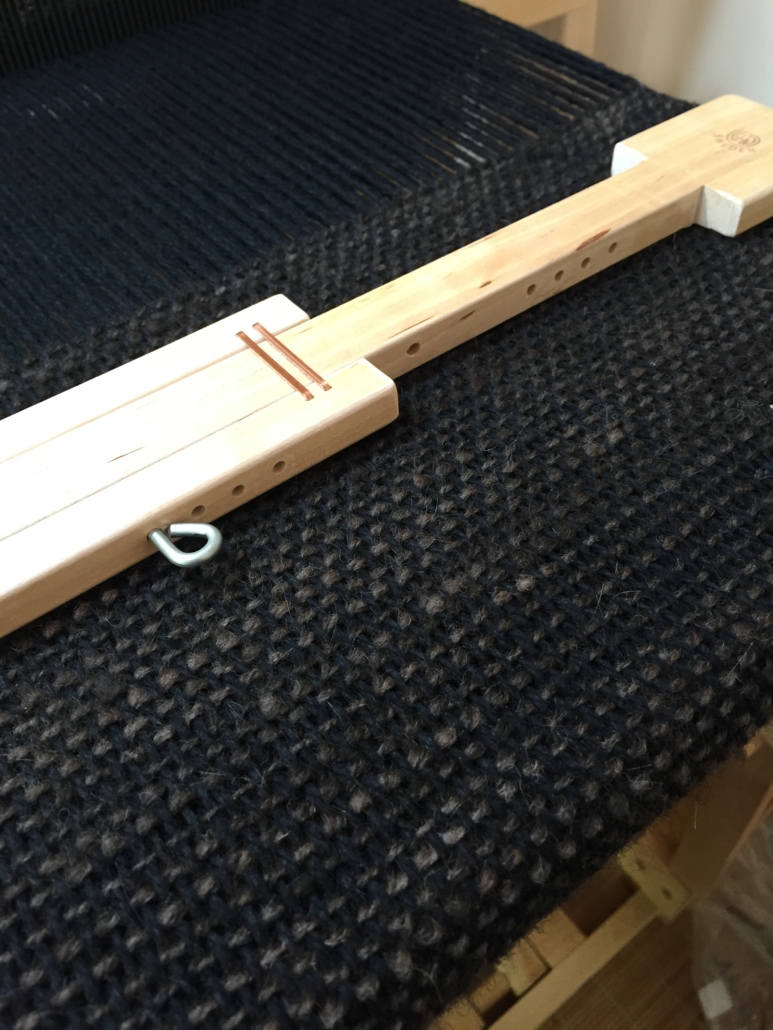

After a bit more thought, I suggested I could spin the yarn and then weave it into a blanket. She liked this idea because she wouldn’t have to sneak around knitting. I wanted it to be a simple design, so I put a plainweave pattern into my iPad Weave It app showing a black warp and the handspun dog fur (with a little alpaca blended in) for the weft. I decided to use Harrisville Highland wool yarn as the warp.

She liked this plan, so I was off and running. Her anniversary was in November, and I had it done in time to enter in the local county fair where I won 1st place. She was tickled to hear that.

Off the blanket went in the mail in time for the anniversary. When I didn’t hear from her shortly after the anniversary, I called her to be sure it wasn’t a disaster or that she wasn’t headed to divorce court. Fortunately, all went well. In fact, she said he cried tears of joy when he saw the blanket. She also said he takes naps under it, and apparently, for the first little while, it shed. In fact, she said it was funny that she was finding little bits of fur in all the places she used to find it when they had the dogs. It was like having them back again. I was very happy for both of them.

I learned a few things from this process. Dog fur is quite heavy by itself. Trying to mimic a remembered color from the animal is difficult because what people remember as the color of the dogs could be their outer coat, not the soft and fluffy undercoat that gets brushed out and saved. Due to my inexperience with spinning an animal fiber, I made a semi-worsted, 2-ply yarn from rolags, which was way too dense and heavy (it’s a wonder they weren’t crushed under the weight of this blanket). And I could have prevented the “shedding” by brushing the blanket while it was still wet to raise the nap and remove any extra fibers that hadn’t been caught in the weave structure.

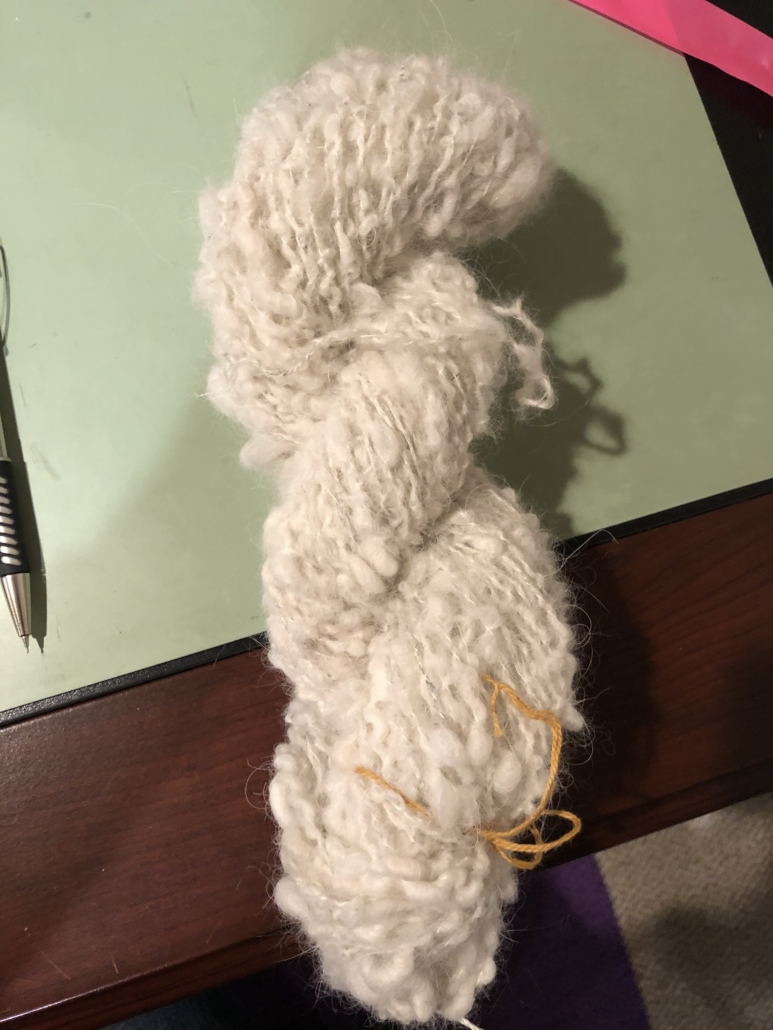

If I were to do this again, I would spin a different style yarn. In fact, I was recently given a bag of English Sheep Dog fur and decided to try my theory of spinning it using a bouclé technique where I lightly spun the fur around a small lambswool core and then plied it with a natural-colored sewing thread. The yarn is light and airy and would weave up into a much lighter-weight blanket with lots of texture.

I really enjoyed this project and was so glad to be able to help a friend give a very special gift.

Liza Jennings Seiner is a handspinner and fiber artist behind Summerhill Spinner who loves to learn about new spinning techniques and apply them to her work. She also weaves and makes braided roving rugs. You can find her under summerhillspinner on Etsy, Facebook, and Instagram, and she blogs at summerhillspinner.wordpress.com.

Check Out Fiber Artist Market

/0 Comments/in Frontpage Article, News, Spinning, We couldn't fit it in the print issue!/by Guest BloggerAs fiber festivals and livestock shows across the United States and many other countries have been canceled, fiber artists and businesses have seen their sales plummet. And festival goers aren’t able to see all of these fiber artists in one place. Fiber Artist Market is a new online marketplace for fiber producers and fiber artists, created shortly before the COVID-19 closures and is currently free for vendors.

Mary, the organizer behind the website, has been involved in the fiber community since she started knitting 30 years ago and has been working with shepherds in her local area and has sponsored FFA/4H kids with fiber animals. Her town has a K-12 Montessori farm school, where she volunteers to teach a “sheep to shawl” every year: the kids raise their own sheep and take classes on everything from animal husbandry to labor law and economics. Then the fleeces from shearing are made into products that are sold at the weekly farmer’s market. Mary’s studio has a micro mill, and they process about 50 fleeces a year and hold classes on spinning, dyeing, felting, weaving, etc. They are the Inland Empire Fibershed SoCal.

Here’s the story of how Mary decided to start Fiber Artist Market, in her words:

I go to a lot of fiber festivals and livestock shows, and over the years I have been impressed with the number of farmers who have sheep and a huge backlog of fleeces in their barns. I frequently buy them and have them processed into yarn, which we then sell at the local fiber festivals, or I try to buy and resell fleeces. Finally it occurred to me that we need an online site to cater to these small hold farmers and independent fiber artists. I found a few friends who were willing to pitch in some start-up money with me, and we got the website started. Our goal was to have it pay us back the start-up cost and then if it made any money we would be able to do FFA/4H grants, internships, scholarships, herd funds, contribute to Livestock Conservancy, things like that.

It took some time as we made lots of mistakes and missteps along the way finding a multivendor platform and all the other things that go into making a website work. Fortunately a local IT guy is willing to work with us for a pittance! We launched it in September with the goal of getting FFA and 4H students’ fleeces online and helping them with some income. Then some local shepherd(esses) asked to be on it and then some of my friends from Black Sheep and Oregon Flock and Fiber, so we said “okay, we can open to the public and see what happens.” We set our prices so they would be affordable for everyone and had subscription packs that would work just for shearing season, a month at a time, whatever anyone wanted to do.

Then came COVID-19 and this whole crisis. Our fiber festival, our farmer’s market outlet, WEFF, Maryland Sheep and Wool all started canceling and suddenly numerous fiber producers and independent fiber artists were locked out of their usual outlets. Because we are small, self-funded, and do not rely on income from the site, we were quickly able to agree to make the website completely free to fiber producers and independent fiber artists. We project we can continue to underwrite the costs of the website, IT, licensing, etc. for about 6 months and then re-evaluate what we need to do. That should take us through the fall shearing season and hopefully the viral crisis will be abated by then.

Since that decision we have just been working on how to get this out to people who might be vendors or buyers and give them the opportunity to sign up and set up their own store. The site is a secure site, SSL covered, with secure payment pathways to the vendors, and privacy is protected as stated in our privacy statement. We are very concerned about getting any spam postings so are keeping a close eye on that and will remove any immediately. We have some great vendors already but have essentially unlimited space for more.

So, if you are a fiber artist, please take some time to see if Fiber Artist Market might be a good fit for you. And if you are a buyer, please check out the offerings on Fiber Artist Market (and check back frequently as new vendors and items are added). Finally, please spread the word about this marketplace. Thank you for your help.

Show Off Your PLY Support!

/0 Comments/in Frontpage Article, News, Spinning, We couldn't fit it in the print issue!/by Guest BloggerAlthough we’d love to see you in person to give you your PLYAway shirts, you can still get one by ordering through our website.

You can also show off your PLY spirit with an awesome PLY shirt.

Thank you so much for all the support you have shown for PLY and PLYAway. We truly could not do this without you!

PLYAway 2019 Scholarship Winner Experience

/1 Comment/in Frontpage Article, Spinning, We couldn't fit it in the print issue!/by Guest BloggerWords and Photos by L’ubica Noemi Kovacilova

L’ubica was the scholarship recipient for PLYAway 2019, which was sponsored by The Woolery. We asked her to write a few words about her experience.

Warning – this article might be slightly biased because as soon as I think of the visit in Kansas City, even with almost a year gone by, my heart is swept into a whirlwind of beautiful memories. It was the first scholarship I have won, my first trip to the USA, and my first trip related totally to spinning. For the past couple of years, with no sources to learn modern spinning in my own language, I have relied extensively on English-speaking videos, podcasts, lessons, and literature. I have discovered PLY Magazine and Jacey Boggs Faulkner as well as books from Sarah Anderson, Deborah Robson, Alden Amos, Jillian Moreno, and many others – and here I was to meet many of my celebrities in person.

I come from Slovakia, central Europe, where I try to make a living with fibrecraft for me and my 3 sons. I have been spinning since 2011, gradually intensifying my learning curve. My work consists of commissions, selling handspun yarn and knitted items at markets, and teaching basic courses on hand-processing wool from raw fleece. The sweet spot of my work, however, belongs to reviving breed-specific local wool and contributing to its return to local market (the number of mini-mills that process local wool in Slovakia is actually zero), and that means a lot of propagation and education is necessary. With other wool-loving friends, we have founded a non-profit organization which tries to bring this almost lost craft back to the public.

Slovakia is a very small country of 5 million. We are quite used to the world not knowing much about us. Therefore, I was pretty amazed when at least 6 people in Kansas City told me that they know their ancestors were of Slavic origin and came from our part of the world. No wonder it felt so home-like. In Slovakia, as in many other countries around the world, handspinning has been almost forgotten for more than half a century. Although the communist regime was strong on industry and self-sufficiency of the country (which means there were several spinning factories) and there was some endeavour to keep the traditional crafts, there seemed to be no particular attention dedicated to handspinning. At the beginning of the 20th century, people in rural areas were still handspinning for factories, but I gather that once all this work was done by machinery, they were happy to get rid of the hard chores – it is indeed very different whether you spin because you must or because you want to. However, one of the unfortunate effects of the postrevolution era was the gradual decline of the spinning and wool-processing factories, which had a negative effect on the work of shepherds, the type of sheep breeds kept, and the price of wool.

Since PLYAway 2019, I have finished and published a brochure on spinning via a local traditional-crafts–keeping organization, ÚĽUV. This little publication is the first tutorial in the Slovak language about hand-processing sheep wool. It helps me greatly with spreading the word about how important and rewarding rediscovering this fibre craft is in our country, where the wool industry is almost gone. PLYAway gave me the confidence to continue, even if making a living in spinning is no easy task – but it is much more precious to me to need less and do the work that makes sense, than having all the comforts and keep losing the precious time of my life to a faceless corporation. Up to this day, all the passion and sincerity keeps me going because I saw it is possible to make a fibre craft really alive amongst the people.

There are moments I am never going to forget: The day spent in the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City, where I exhausted my wonderful host and guide Teri Plemel because it was such a breathtaking walk that I just couldn`t stop watching. The first evening in the hotel, when I met Jacey and Jillian. The meeting of the attendees in the hotel‘s pizzeria, when I sat near two wonderful ladies, who after learning of my limited budget told me to pick something at the fibre market and tell them and they would get it for me (and learning to spin cotton in their hotel room one midnight). Jillian Moreno taking pictures of the members of her class as we rolled around in her hilarious stash of fibers spread on the carpet. The experienced hands of Joan Ruane, spreading flax and dressing the distaff. The piece of fluff that Stephenie Gaustad placed on carders while she told us we should never hear the tines scratch while carding. The cooperation of the whole group while dyeing wool with Jane Woodhouse. The little talk with Gord Lendrum about his wheels. The whole Shave ’em to Save ’em booth and how a little present I brought from Slovakia kept us in contact with Amy and allowed me to watch her strength during the past year.

I realize how little really I do know – of the textile industry, shepherding, sheep, wool, economic relations, trade, etc. There is so much to be done about reviving wool as a natural and sustainable material in Slovakia, and much of it is beyond my capabilities. But the big thing for me personally is that I can contribute my share to the process. With the knowledge I have accumulated overseas, with the new book published, with courses, with all the debates at the fairs and markets I attend, I can get the visitors intrigued by all the wool knowledge that almost vanished from our collective mind.

I am blessed to have been able to go. As the world slows down this year and because of the raging virus, so many events are postponed. I keep my fingers crossed for all the wonderful work around PLYAway not to be in vain.

I can hardly describe how much I have enjoyed the whole retreat. It was a delight to see how much I was able to learn in advance from all the sources in print and online, so I could cope with the pace of the lessons, and at the same time discover so many new things I didn’t even know I didn’t know 😀 But most of all – the friendliness and generosity of the fibre community exceeded my expectations by far. I was so far from home and yet felt so very much at home – I bet you know exactly what I mean. 🙂

How to Make the Best of It: Commemorative Skeins for a Beloved Pet

/in Frontpage Article, Spinning, We couldn't fit it in the print issue!/by Guest BloggerSmall Batch Yarn Prep

/0 Comments/in Frontpage Article, Spinning, We couldn't fit it in the print issue!/by Guest BloggerWords and Photos by Margaret Wright

Three years ago, I went from a Jersey Shore schoolteacher and suburban mom to living in the woods of Western Maine. I purchased my first spinning wheel and joined an amazing group of people in a spinning group out of Cornish, Maine. They insist they love me despite the way I say coffee and dog, and they totally took pity on my lack of fiber knowledge, taking me under their wings. They truly are my fiber angels. It was from them I learned how to prepare small batches of fiber.

After buying a few really dirty and stinky fleeces, I decided I really hated the whole process of cleaning the poop parts off the fleece, known as skirting. So I now purchase my fleeces at fiber festivals or at reputable fairs as they are usually skirted and much better quality. Although the fleece still has some poop, there’s a whole lot less of it. At the Fryeburg Fair in Fryeburg, Maine, I purchased a very nice Romney fleece. I prepared the fleece in small batches for spinning.

Supplies

I recommend using a double sink, but you can improvise and use a single sink. You’ll also need Dawn blue dish soap, really hot water, a salad spinner, and some sort of rack to dry your fiber on. I have used a dog crate, a fireplace screen, and lawn chairs! Improvise is my middle name. I also wear gloves as I like really hot water, and, oh yeah, I hate poop.

Process

I squeeze 3 to 4 circles of Dawn into my clean sink after making sure the stopper is in. You do not want too much soap or it will be too sudsy. I then fill the sink about 3/4 full of the hottest water I can get from my tap.

I gently pull a chunk of fiber off the fleece, making sure to remove any straw or poop. Then I gently submerge my fiber into the hot water. Be careful not to agitate it or it will turn into felt like you buy in the craft store.

I set my timer for 30 minutes. Then I go do whatever. Pet the dog, have a coffee, whatever. After 30 minutes, the water will be dark and nasty looking due to the combination of dirt and lanolin that occurs naturally on wool. I unplug the drain and gently press the water from the fiber. I like to press it against the side of the sink. I know I say gently often, but it really is important to be gentle.

At the same time, I have the second sink filling with clean, very warm water, but not as hot as the first sink was originally. I submerge the fleece gently into the clean water and allow this to sit for 30 minutes also. If you don’t have 2 sinks, put your wet fiber in a bowl or pot while you refill the sink with clean water.

Note: I like my fleece a little greasy, meaning I like to spin it with more of the natural lanolin in it. My friend washes it twice, repeating the first wash, as she likes her fleece really clean. Try both and see what you like best.

I drain the rinse sink, gently press the water from the fiber, and divide the fiber into smaller batches that can fit in the salad spinner. I place the wet fiber into the salad spinner and spin it twice, one time in one direction and the second time in the other direction, dumping the water out in between spins.

Prep for Spinning

Once your fiber is dry, you can prep it for spinning a variety of ways. As you gain more experience and become more comfortable, you may want to try different methods to prep your fiber.

For spinning prep, the easiest way for a newbie like I was just 3 short years ago is to do what is called flicking. I love to sit in the evenings and flick the ends of my fiber locks open using a dog comb. To do this, I firmly hold one end of 1–3 locks, depending on thickness, and gently pull the dog comb over the ends until the tips are nice and fluffy. I then turn the fiber around and repeat the process.

You can also use a hand carder or a dog brush to open up the fiber ends. I find this very relaxing in the evening when my husband is mesmerized by his Bigfoot shows and I listen to an audiobook. When we go places, I frequently take fiber with me. I combed enough fiber one night watching our son play lacrosse to spin 75 yards. Plus, it’s a great icebreaker as people will come up to investigate and you end up meeting some great people.

Margi Wright lives in Maine where she sells baked goods and fiber products at a local farmers market, a switch from her former Jersey Shore life as a teacher. Margi enjoys an active lifestyle completing triathlons, cross country skiing, and traveling with her husband to see her children and grandchildren.

Prepping Fiber for a Large Project

/0 Comments/in Frontpage Article, Spinning, We couldn't fit it in the print issue!/by Guest BloggerWords and Photos by Anne Schwarz

I’m making my first sweater from scratch.

This is new for me. Usually I spin a pound of this, a 4-oz braid of that, enjoying the pretty colors or trying my hands at a technique or a yarn design idea, and then I make yet another hat or scarf. In fact, I just finished another 284 yards of a pretty blue and yellow yarn from fiber that caught my eye at a vendor booth, destined to become something, someday. The joy is in the spinning, right?

Well, for a new challenge, I decided a few months ago to try my hand at spinning for a large project. The challenge was consistency – how could I make a couple thousand yards of 2-ply yarn that would look cohesive when knitted up, without disruptive shifts in color, thickness, or texture?

Consistency starts with the fiber prep.

I chose a 70% alpaca/30% Merino blend for my project because I had a lot of alpaca fleece in my stash in a few different colors. Because 100% alpaca yarn is notorious for stretching out over time, I wanted to blend it with some wool to give it some memory. Whenever I think about blending fibers, I consider what traits I’m adding and why. I chose Merino because it’s a fine wool and would not detract from the alpaca’s best quality, its softness.

Planning My Colors

As I washed and picked through about 2 pounds of alpaca fleece, I put it in 2 large piles; one was a mix of white and light beige, and the other was a mix of natural shades of brown.

There are 2 breeds of alpaca: Huacaya, which is a fluffier, crimpier fiber, and Suri, which is smooth and shiny and has a lot of drape but no crimp. I used mostly Huacaya for this project, but I had a bag of luscious dark brown Suri locks, and I couldn’t resist adding a couple of handfuls to the brown mix, as I thought it would add interest to the yarn.

I knew I was going to leave the brown alpaca its natural colors, and eventually dye the white/beige mix. I settled on a sweater pattern that could be made with either 2 or 3 colors.

The Merino I had was white combed top. This would blend in beautifully with my white alpaca blend, and I had the option of dyeing all of the fiber before blending, after blending, or after spinning. What would give me the most consistent color? Probably dyeing all of the fiber before blending because any inconsistencies in color would be blended together. But indecision got the better of me – I wasn’t ready to choose a color yet, so I decided to wait and dye the finished yarn.

The brown alpaca mix was a different story. I didn’t want to blend white Merino with colored alpaca because it would just dull and lighten the rich natural colors. In this case, I decided to dye the Merino before blending, using colors that would complement the alpaca’s shades of brown. I handpainted a length of Merino top with acid dyes in burgundy, a basic red, a rusty red, and golden yellow, plus a bit of brown that was darker than the alpaca and would blend color with color.

Prepping the Fiber Before Blending

While washing and picking my alpaca fleeces, I found my fiber had some variation in staple length (up to an inch difference), and the Merino was similar in length to the longer alpaca fibers. This pointed me towards a carded prep because combs will separate shorter from longer fibers, while carding creates a web of fibers of different lengths, going in different directions. I used a drum carder for both carding and blending.

The first step was carding the alpaca and Merino separately. I’d washed the alpaca and picked out most of the VM, but it needed a couple of passes through the carder to transform the locks into a loose web of fiber that would blend easily. This step also blended the white and beige fleece into an off-white color and the various shades of brown fleece into a gorgeous variegated brown.

I also put the Merino through the carder once on its own, even though it was already processed as combed top. Commercial top can be kind of dense and compressed, and a pass through the carder loosens and opens it up beautifully. In my experience, it blends with other fibers much better that way. However, with my handpainted Merino, this pass blended the colors together more than I wanted, into a sort of reddish brown. It wasn’t bad, but if I had it to do again I would dye the Merino in small single-color batches. I would then run these through the carder separately at this stage, and I would blend in the next step with the brown alpaca.

Blending

Now I had 4 stacks of batts – off-white alpaca, white Merino, brown alpaca, and reddish-dyed Merino. Each stack had several batts. I’d weighed out my fiber ahead of time, so I still had 70% alpaca and 30% Merino in each color group. The next step was to blend them so the fiber ratio was consistent across all my batts.

I put the white batts in one big stack, alternating layers of alpaca and Merino, and then divided the stack into vertical cross-sections that were each about the amount I could comfortably fit on my carder. I put each cross section through the carder and then stacked the batts again and repeated the cross-section process. This method blended the fibers fairly well and evened out any inconsistency.

I used the same method with the colored Merino/brown alpaca. It was all nicely blended and ready to spin.

A Few Notes on Spinning and Dyeing

It took me a few weeks to spin the yarn for this project, but I must say the spinning went faster than the fiber prep!

Before spinning, I finalized my pattern choice, selecting Coiled Magenta by Carol Feller of StolenStitches.com. It’s a loose, V-neck sweater that uses 2 colors and some cool color blocking. It calls for 2 colors, but I’m going to use 3 because in the end I divided my white yarn into 2 colors.

I dyed the white yarn 2 different colors for a simple reason – the limited size of my dye pot. I had to dye it in 2 batches, and rather than making 2 dye lots of the same color that might not match, I decided to do a blue and a green. The green dyed a little bit unevenly, and in retrospect it might have been better to have dyed the fiber before blending and spinning, but I think the darker areas are well distributed and will look consistently inconsistent when knitted up.

I had noted the thickness (12 WPI) and grist (approximately 1300 YPP) of the commercial yarn suggested for this pattern. I didn’t achieve the same grist; my brown yarn is the same thickness but is a little heavier, probably because I included some Suri alpaca. Suri just has no loft to it and made for a bit denser yarn. But I made a couple of swatches, and I’m happy with the gauge and the feel of the cloth so I think it will work nicely.

Conclusions

I’m very excited about how my yarn turned out, and I’m really glad I took the time to prep the fiber with quantity and consistency in mind. I also benefitted from studying the yarn suggested for my chosen sweater pattern so my handspun yarn would work as a substitute.

And I learned a few lessons.

First, the addition of Suri alpaca, even though it was probably no more than 10% of my yarn, made a real difference in the grist, producing a heavier, denser yarn than a similar blend without Suri. Second, I wish I’d dyed my Merino in small single-color batches before blending, instead of one long hand-painted piece of top – it would have prevented it from getting over-blended, and I’d have had a bit more color variation in my brown yarn. And last, I have more to learn about dyeing a large batch of yarn with even color, so it might have been wiser to dye the fiber at the beginning of the project, before blending.

Anne Schwarz started spinning 11 years ago after buying a soon-to-be mama alpaca, along with a bag of her prize-winning fleece. She found a beginner spinning class and a world opened up. She no longer owns alpacas, but their wonderful fiber is still her favorite.