Reader Feature: Chantily Lovelace

Chantily posted on the PLYAway board on Ravelry about the “classes” she was taking at home since PLYAway was canceled, so she’s here to share a little bit about that with you as well as a little more about herself.

Tell us a little bit about yourself and how you got started spinning.

I’ve been playing with string for as long as I can remember – making webs in the living room of the mobile home my dad had bought from his brother and tying the front door into my web so Mom had to cut it before Dad could get in when he came home from work. I learned to crochet from my mom who taught me what she learned in evening classes. I learned to knit from a 4-H project manual. Spinning seemed magical when I saw it happen, when a former coworker pulled out a drop spindle. Twelve years ago, I demonstrated weaving on an inkle loom at Shepherd’s Cross Farm outside Claremore, OK, and made an acquaintance who was gracious enough to host me for a weekend and pay for me to spend a day learning to spin on a wheel, an Ashford Kiwi. I bought a drop spindle and got going in 10 minutes (I learned how to start without a leader and took off). I have not stopped since.

Do you have a favorite type of yarn to spin?

My default is somewhere between a thick fingering and a thin DK. I generally prefer a smooth yarn over art yarn. I have been working on intentionality, deciding beforehand what yarn I want using tools that measure for consistency. The latest is attempting to duplicate the weight of a commercial yarn recommended for a particular cardigan, Koronki, that I picked for a MeMadeMay challenge of meeting the criteria of including red, mohair, and a pleat. Fibers I love spinning are BFL and Cormo. Luxury fibers are cashmere and paco-vicuña, not that I get them very often.

What do you like to make with your handspun yarn?

I have no particular garment or accessory I prefer in handspun. When I started spinning I chose to buy fiber over yarn for getting more enjoyment for my money. My first handknit out of handspun was the Adamas shawl out of a thick lace/sock weight yarn from mohair, shetland, and alpaca that I hand blended with combs.

How long have you been reading PLY?

I’m a newer reader of PLY, looking it over after taking my first class at the 2nd PLYAway. I susbcribed and ordered back issues after PLYAway 5 was cancelled. I’ve been reading those since, looking through the issues most relevant to something I’m doing.

What do you look forward to most when you get an issue?

I’ve enjoyed articles written by PLYAway instructors I have taken classes from – as a way to refresh what’s rolling around in my head from class.

Tell us about not being able to have PLYAway and what you did instead.

I was so hoping COVID-19 would not affect (or minimally affect) PLYAway. It’s my one big fiber event. I don’t travel well, so having something this big so close is wonderful beyond words. I can count myself fortunate that the canceling of PLYAway was my only sorrow in the pandemic, but still, I was heartbroken. I get so much new learning to incorporate and work with over the rest of the year, and it’s the one event where I feel energized by being around people because I’m with people who share my favorite thing to do.

When PLYAway week approached, I decided to do “PLYAway At Home”: I wore my T-shirts and plotted out some activities I knew would take at least a day to do and some that would be a challenge. One day was “Learn to Love the Dealgan.” I watched Lois Swales’ “Spin Like You’re Scottish” on YouTube and then ordered a shorter, heavier dealgan to see if it was me or the tool. A heaver tool with a shorter neck worked better; it’s a bit of a wobbly thing.

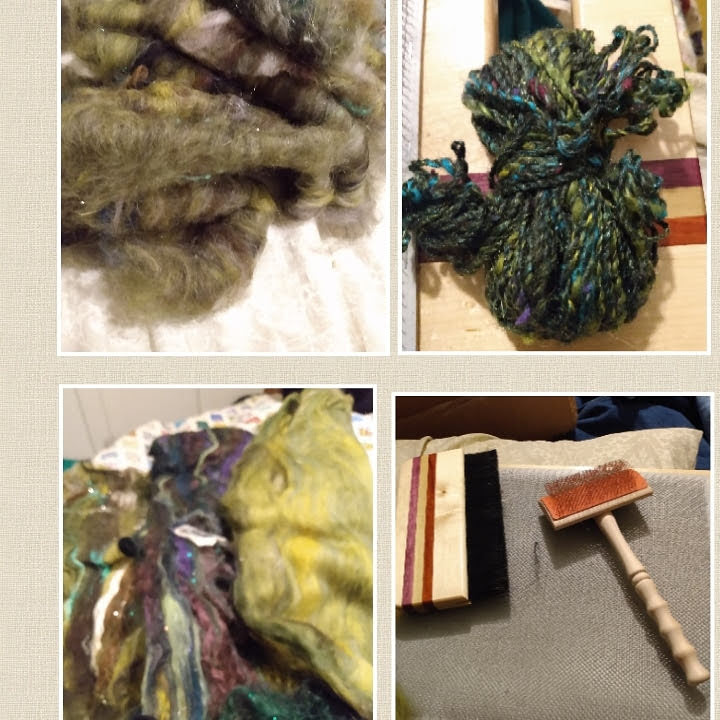

I spent a day blending a batt on a blending board and making rolags, attempting to come close to replicating a tiny sample of yarn I wanted more of.

I spent time finishing some Cormo wool I had prepped and spun earlier. Hot soak, twacking, and a cool rinse led to blue fluffiness.

I couldn’t pass up experiencing Spin & Nosh (mostly noshing), so bought sheep milk cheeses from The Better Cheddar – shoutout to Green Dirt Farm’s spreadable sheep cheese.

And then, shopping! Live virtual shopping at Spry Whimsy got me 2 Uncharted Waters spindles and Essential Fibers roving.

The Natural Twist was very happy to custom blend big batts, using pictures of spring colors that I sent.

The 100th Sheep had gorgeous colors in Cormo – yes, I’m in love with Cormo.

I also bought pansy-themed yarn from Fairy Tailspun Fibers, blue & white from The Fiber Sprite, the PLYAway color from Essential Fibers, and yarn from Greenwood.

I certainly hope PLYAway can happen next year. In the meantime, I have a whole lotta spinning.

Chantilly Lovelace is the outreach chair for the Fiber Guild of Greater Kansas City. You can find her as Chantillylace on Ravelry.

If you’d like to participate in an upcoming reader feature, fill out the reader feature form and Karen will contact you.