Mixing Things up for a Sweater

words and photos by: Johanna Carter

I always admire those who are able to spin mountains of yarn for a big project, ready to knit a wonderful sweater or cardigan. It is a satisfying feeling when you finish all that work, especially if you started with washing and combing the wool or even raising your own sheep.

Mixing spinning and knitting

The typical way to work through a larger project is to spin all the singles first and ply them in a particular order so you get the yarn even throughout the whole project. I don’t have so many bobbins, but my bigger problem is that I am quite impatient and want to get on with knitting once I have an idea. And normally, my brain is full of ideas for fibre work and the limit is the time, as I am a musician and teacher. I can’t sit at the spinning wheel for a long time if I’m not on holiday, so during the school year I mostly knit, and during the holidays I can dye, spin, use my drum carder, and do lots of fibre work. The only time I was able to produce bigger quantities of yarn before I knitted them up was during the Tour de Fleece in the two years during the pandemic, when we did not go on holiday at the beginning of July.

I like to finish knitting one big project like a sweater or cardigan before I start the next one, or at least until I can’t carry it in my bag easily anymore, so I have an excuse to begin the next one. Sometimes it is good to have a second project on the go – I call it mindless knitting, where I don’t have to look very much – which I can keep my hands busy during Zoom or other meetings, which helps me listen.

Mixing colours and fibres

Usually I dye my yarn with plants which I collect in the woods or get from garden flowers. I also use cochineal and indigo, which I buy, to get lots of different colours. I really love the greens and blues I get from dyeing with indigo. I have lots of dyed wool, and all those colours give me inspiration for further projects.

Blending the wool on the drum carder I can get even more shades. I like to blend with fibres like silk, alpaca, or plant fibres, and I love sari silk, to get those little bits of colour in my yarn.

When I have an idea for the next sweater, I start carding, and then I can begin to spin. Once I have spun enough yarn – say, for one day – I cast on and start knitting, usually top down, so I don’t have to decide too much in advance about length and width.

When I spin on my wheel, I have to sit at home, but while spinning I can read a book or talk to others during online meetings. I also like to spin on my spindles, and that works on a walk, or a museum visit. I take them on holiday as they don’t need much space, and when I spin for a lace shawl, I don’t even need much wool either. At home there are spindles all over the place; I can spin when I am waiting for the kettle to boil, when the computer is slow, when I am cooking. Like that I can make good use of a short time and the yarn still grows.

I can take my knitting almost everywhere, which is why I don’t want to wait to get started until I have spun all the yarn for a whole sweater. I knit at home, on the bus or train. The only thing I have to make sure of is to be one step ahead with the yarn.

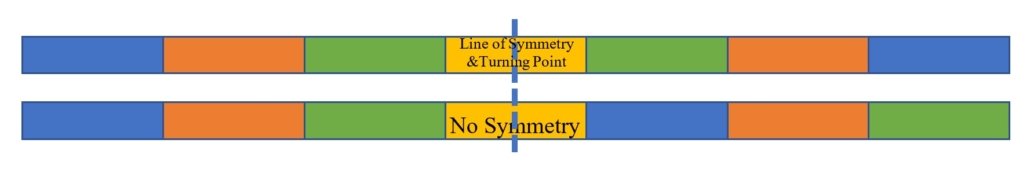

I love to knit Fair Isle sweaters. My favourite method is to use only one bobbin, which I don’t even fill, because I need smaller quantities of lots of colours. Then I wind a ply ball and ply it on itself. For that I put my thumb through the ball, so I can tension the two singles with my fingers and they don’t get tangled, as long as my thumb (or a cardboard roll or a pencil) stays in the middle. I don’t have any leftovers from plying, and it is quick when I suddenly need more yarn.

I have never had problems with the yarn not being consistent enough throughout a project. I just know what yarn I want and my fingers seem to remember what to do. I am sure it is good advice to have a little card tied to the spinning wheel with a bit of the singles you are aiming for, so you can check and make sure you are spinning a consistent yarn.

Mixing breeds

There are so many different breeds, but some of my favourites are Shetland, BFL, and Jämtland – a Swedish breed. After dyeing them, I often forget what I have used, so when I do a new project it often turns out that I have used different breeds and fibres just to get the right colour. For the Fair Isle knitting I want to juggle lots of colours, which is more important to me than making a sweater out of only one breed.

Recently I made a pullover for my husband using about 12 different breeds and colours, even mixing short and long draw. For me it was a breed experiment and a way to use up lots of smaller quantities of wool I had in my stash. For that sweater I used combed top without blending.

Mixing in knitting during the spinning process is a wonderful way for a spinner to avoid being overwhelmed during a sweater project.

My feeling is that some people don’t dare to start spinning for a bigger project because they get overwhelmed by the quantity they have to spin and then all the knitting there is to do, especially when you want to spin the yarn entirely on spindles. Mixing the spinning and knitting for the same project is more interesting; you get more variety and more freedom to choose what you want to do next as long as you don’t run out of yarn. It breaks the project down into smaller, less daunting parts. The only thing you might want to plan is to have enough fibre at the start, but even that is not necessary, there is always a sheep growing more wool.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!